The Complete Truth About Plant Protein Quality

WHAT THE BEEF AND DAIRY INDUSTRY DOES NOT WANT YOU TO KNOW

The Rise of Plant Protein

If you look at a list of ingredients consumers want more of in their food, protein would be among the top. In fact, 25% of consumers would choose protein as the ideal ingredient to fortify their favorite foods with according to recent Mintel data. Protein is essential to life and nourishes nearly all body systems. And beyond that, research has shown that protein-rich diets hold benefits for weight management, appetite and blood sugar control making it a supremely attractive nutrient for today’s ‘I want to age stronger and healthier’ consumers.

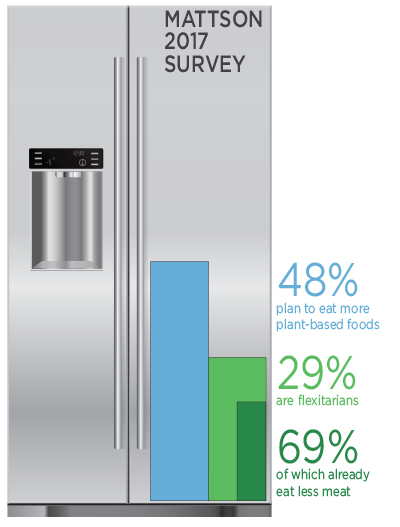

But Americans aren’t necessarily looking to eat more meat and chicken breasts to boost their protein intake. Driven by fears about eating too much meat paired with concern for animal protection as well as the environment, they are increasingly turning away from animal-derived proteins and toward more plant-based alternatives. According to a Mattson survey from 2017, almost half (48%) of respondents said they plan to eat more plant-based foods in the future, while almost a third of respondents (29%) considered themselves flexitarian with most (69%) already cutting down on meat.

But Americans aren’t necessarily looking to eat more meat and chicken breasts to boost their protein intake. Driven by fears about eating too much meat paired with concern for animal protection as well as the environment, they are increasingly turning away from animal-derived proteins and toward more plant-based alternatives. According to a Mattson survey from 2017, almost half (48%) of respondents said they plan to eat more plant-based foods in the future, while almost a third of respondents (29%) considered themselves flexitarian with most (69%) already cutting down on meat.

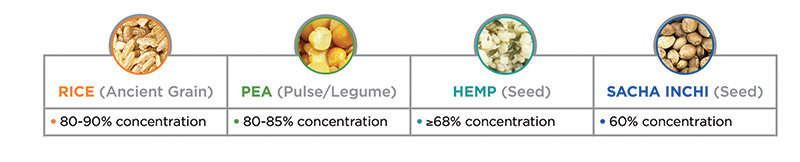

While soy once reigned as the top plant protein choice, today dozens of other options have emerged and are making their way into more than just protein powder supplements in specialty stores. Plant proteins such as hemp, rice, pea, sacha inchi and pumpkin seed are being used to fortify everything from non-dairy milks to savory snack foods like popcorn and even desserts like ice cream. Plant protein has become a top-selling ingredient cross all channels according to 2017 SPINS data.

As the number of people powering up on plant protein continues to grow, so does interest in understanding their quality. Are they as effective as animal proteins? Do they need to be combined with other protein sources given their “incomplete” amino acid profiles? Here is the complete truth about plant protein quality.

But First, Why do Consumers Want More Protein?

Protein holds multidimensional benefits but among the most recognized are its abilities to help build  muscle, support weight loss and provide nourishment for healthy hair, skin, and nails. As more consumers challenge themselves to become stronger and healthier, they are seeking more protein from healthier sources. According to the International Food Information Council (IFIC), 66% of Americans tried to consume more protein or as much protein as possible in 2016.

muscle, support weight loss and provide nourishment for healthy hair, skin, and nails. As more consumers challenge themselves to become stronger and healthier, they are seeking more protein from healthier sources. According to the International Food Information Council (IFIC), 66% of Americans tried to consume more protein or as much protein as possible in 2016.

Other major functions of protein in the body include:

- Building valuable enzymes that regulate daily bodily functions (like digestion and the sleep/wake cycle)

- Transporting nutrients, oxygen, and waste throughout the body

- Building antibodies which support the immune system

- Building hormones such as insulin to regulate blood sugar

- Forming new cells by reading genetic information stored in DNA

Plant Protein Advantages

Forty-six percent of Americans agree that plant-based proteins are better for you than animal-based options according to Mintel. While this perception may hold true for whole plant protein sources, many wonder whether the same can be said for concentrated plant protein powders.

One thing is for certain: plant proteins are naturally free of saturated fat and cholesterol whether concentrated or not. This makes them attractive ingredients when formulating for general wellness and heart health, one of America’s top health concerns. Unlike animal proteins, they’re also free from contamination of growth hormones and antibiotics that may be used on livestock.

Being free from allergens is also an advantage of plant proteins as they offer alternatives to egg and milk-based proteins (like whey) which are two of the top 8 allergens. Up to 15 million people have food allergies in the US according to Food Allergy Research & Education. Additionally, 65% of the human population has issues digesting lactose, a milk sugar found in all dairy products and in most dairy-based protein concentrates.

Some plant protein powders provide protein and nothing else, whereas others may retain some beneficial nutrients from its parent material depending on the degree of protein concentration and processing method used. For example, hemp and sacha inchi protein powders with only 50-70% protein still contain a range of vitamins, minerals, some fiber and even essential fatty acids like alpha-linolenic acid, offering a multi-benefit ingredient for formulators and consumers alike. Eighty to 90% protein concentrates such as rice and pea protein have little of any other nutrient and are best for fortifying protein content alone in formulations.

Plant Protein Quality

Protein quality, defined as the ability of a protein to provide the body with amino acids in needed ratios to achieve protein synthesis is currently measured by the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). It is determined by comparing a protein’s amino acid profile to a standard reference protein (aka a scoring pattern) and then taking into account its digestibility—the percent of the ingested protein that is actually absorbed by the body. The resulting value essentially tells us how well a single protein source is able to sustain new tissue growth in humans. But when do humans ever consume a single type of protein all day long?

There are very few instances, one of which is during infancy. Needless to say, therein lies one of the commonly disregarded limitations of the PDCAAS which is important to note when dealing with plant proteins. It is imperative for formulators, clinicians and consumers alike to keep in mind that PDCAAS is purely mathematical and does not provide real world application of protein utilization. Plant proteins are expected to have lower PDCAAS values than animal proteins given their incomplete amino acid profile and subpar digestibilities. But the reality is that these less than ideal PDCAAS values of individual plant proteins are irrelevant within average adult human diets which are composed of 5 or more protein sources per day. It is a known fact that the human body combines amino acids from multiple protein sources in a 24-hour period in order to activate protein synthesis.

The Proof is in the (Protein) Pudding

Multiple studies to date have compared the efficacy of a plant protein to animal-based whey protein when used as a post workout supplement. In 2013, Joy et al. determined that administration of Oryzatein® rice protein post resistance exercise improved body composition and exercise performance, as good as whey protein did, in groups of trained athletes. Specifically, both supplements worked equally well to increase lean body mass, muscle mass, strength and power. There were no significant differences between groups. This study was published in Nutrition Journal.

Supplemental pea protein was shown to promote increases in biceps brachii muscle thickness as effectively as whey protein in a 2015 study published in Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. Participants underwent 12 weeks of resistance training and were instructed to consume pea protein, whey protein or placebo twice a day during their training period.

A 2018 study on professional mixed martial artists (MMA) found no benefit of whey protein over rice protein (or vice versa) for building and maintaining muscle mass. Participants underwent high intensity and interval training for 6 weeks which included two standardized MMA style sessions per day five days a week along with two strength and conditioning sessions per week. The study is published in EC Nutrition.

Most recently, researchers at Lindenwood University examined the effects of a lower, 24g daily dose of Oryzatein® rice protein or whey protein on 8 weeks of resistance training. Similarly, they too found that both proteins conferred the same benefit on training adaptations helping to significantly increase muscle mass and athletic performance. In other words, there was no advantage to using whey protein. This study is published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition.

These studies help to support the fact that incomplete does not mean obsolete when it comes to plant proteins. In spite of incomplete amino acid profiles and imperfect PDCAAS scores, protein synthesis was still achieved especially when consumed as part of omnivorous diets.

Quality Solutions

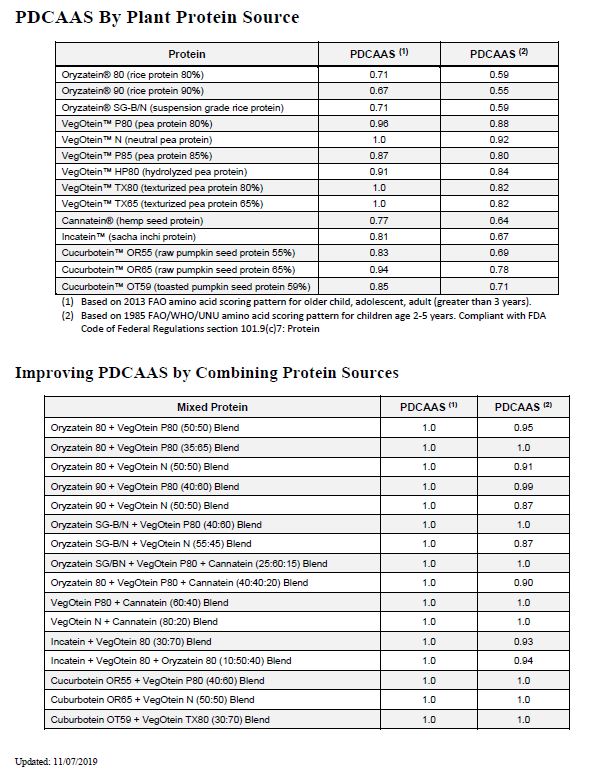

Despite criticisms, the PDCAAS method of protein evaluation is currently approved and required for use by the FDA when making a protein claim on a food label. While animal-based proteins like egg, whey and casein have perfect or near perfect PDCAAS scores (i.e. 1.0 or 100%), plant proteins have presented a challenge to formulators given their imperfect scores.

Formulating with two or more plant proteins is a simple and effective way to improve the PDCAAS value of protein when making a protein claim. Grain-based proteins will generally complement and improve the amino acid profile of a legume-based protein and vice-versa. Seed-based proteins should be evaluated individually, as the limiting amino acid will vary from source to source. Table 2 shows examples of enhanced PDCAAS scores for plant proteins blends.

While it is outdated wisdom that plant proteins need to be consumed in the same meal to obtain necessary essential amino acids, labeling laws have yet to catch up to this fact. PDCAAS values should be considered when making protein claims, but they should not be the tell-all for plant proteins whose other merits outstand animal-based proteins for today’s health savvy and environmentally conscious consumers.

As plant-based eating continues to trend, more plant proteins will continue to infiltrate the market. As such, it is important to understand and evaluate plant protein quality from both a mathematical and nutritional stand point and remember that in light of modern American diets an incomplete protein does not mean an obsolete protein. When it comes to formulating, plant protein quality is easily enhanced by blending with one or more complementary proteins.